Published on 2024-09-08, 1053 words

This year, millions of high school math students will learn about compound growth. Take $1000, put it in a bank account where it earns 5% each year. Because that extra $50 stays in the account, and earns its own interest, you get a little more interest every year.

f(0) = $1000 => $1000.00 f(1) = $1000 * 1.05 => $1050.00 f(2) = ($1000 * 1.05) * 1.05 => $1157.63 f(3) = (($1000 * 1.05) * 1.05) * 1.05 => $1276.28

And, with a bit of algebra to collapse the repeated x1.05 multipliers into an exponent, you end up with this neat formula:

f(t) = 1000*(1.05)t

You can pick any t - any year in the future - and compute your accumulated interest in a single calculation, without needing to tabulate any previous years.

f(15) = $1000*(1.05)15

= $1000*2.078928

= $2078.93

This is where the math teacher, the wise adult, will point out the profound personal finance lesson on the chalkboard. Suppose you, 15 year-old student, work all summer and make $1000. If you take that $1000 and put it in a high-yield savings account that yields 5% annual interest, by the time you’re 30 you’ll have twice as much money!

That’s right, if you just wait until you are literally twice as old as you are now, you’ll double your money… yes, this is the power of compound interest…

Here’s a variant that may be more compelling to that 15 year old:

You have $1000 in-hand from your summer job: go ahead and blow $700 of it on an iPhone or whatever, but invest the other $300. But, after next summer, you need to add another $300. And so on, for the next 15 years, with each previously-invested $300 continuing to yield 5%. The math works out to an accumulation of over $7000 over that same 15 year period: $4500 in principal, $2597 in interest.

The math is a little more complicated. You can think of each $300 installment as its own unit of compound interest. They all compound at the same rate, but each installment is compounding for a different duration. Here’s the brute-force way to calculate it:

| Year invested | Installment | Years invested | Formula | Principal+Interest |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | $300.00 | 15 | $300*1.0515 | $623.68 |

| 2025 | $300.00 | 14 | $300*1.0514 | $593.98 |

| 2026 | $300.00 | 13 | $300*1.0513 | $565.69 |

| 2027 | $300.00 | 12 | $300*1.0512 | $538.76 |

| 2028 | $300.00 | 11 | $300*1.0511 | $513.10 |

| 2029 | $300.00 | 10 | $300*1.0510 | $488.67 |

| 2030 | $300.00 | 9 | $300*1.059 | $465.40 |

| 2031 | $300.00 | 8 | $300*1.058 | $443.24 |

| 2032 | $300.00 | 7 | $300*1.057 | $422.13 |

| 2033 | $300.00 | 6 | $300*1.056 | $402.03 |

| 2034 | $300.00 | 5 | $300*1.055 | $382.88 |

| 2035 | $300.00 | 4 | $300*1.054 | $364.65 |

| 2036 | $300.00 | 3 | $300*1.053 | $347.29 |

| 2037 | $300.00 | 2 | $300*1.052 | $330.75 |

| 2038 | $300.00 | 1 | $300*1.05 | $315.00 |

| 2039 | $300.00 | 0 | $300*1 (no interest yet) | $300.00 |

Summing up the Principal+Interest column yields the total of $7,097.25.

If we generalize and replace $300 with a constant P, and 1.05 with a constant R, our formula (for 15 years) is:

PR15 + PR14 + PR13 + PR12 + PR11 + PR10 + PR9 + PR8 + PR7 + PR6 + PR5 + PR4 + PR3 + PR2 + PR + P

Just add more terms if we need more years.

Surely there’s a more efficient way to do this?

Yes! There is a mathematical technique to shorten this. This type of equation is a well-known mathematical form called a geometric series, with a closed-form sum formula:

F(t) = P * (1 - Rt+1)/(1 - R)

It’s a little more complex than our plain compound interest formula. Let’s try it out, with P=$300 and R=1.05:

F(t) = $300 * (1 - 1.05t+1)/(-0.05) F(1) = $300 * (1 - 1.052)/(-0.05) = $615.00 F(2) = $300 * (1 - 1.053)/(-0.05) = $945.75 F(3) = $300 * (1 - 1.054)/(-0.05) = $1293.04 ... F(10) = $300 * (1 - 1.0511)/(-0.05) = $4262.04 F(15) = $300 * (1 - 1.0516)/(-0.05) = $7097.25 F(50) = $300 * (1 - 1.0551)/(-0.05) = $66244.62

The Coffee Machine that can Pay for a University Education is a case study of a hypothetical two-adult household, where each adult spends $7 on a ‘fancy’ coffee every day. Looking ahead to their newborn child’s college costs, they have a frugality epiphany, and start using an at-home coffee machine to save money. The claim in the article is that if they invest their coffee-savings at 7% annual interest, they’ll have $148,000 after 17.5 years, to pay for their kid to go to college.

When I tried the math, I actually got an even higher figure of $182,000:

1 coffee/adult/day * 2 adults * $7/coffee * 365 days/year = $5110.00/year F(17.5) = $5110.00 * (1 - 1.0718.5)/(-0.07) = $182,224.73

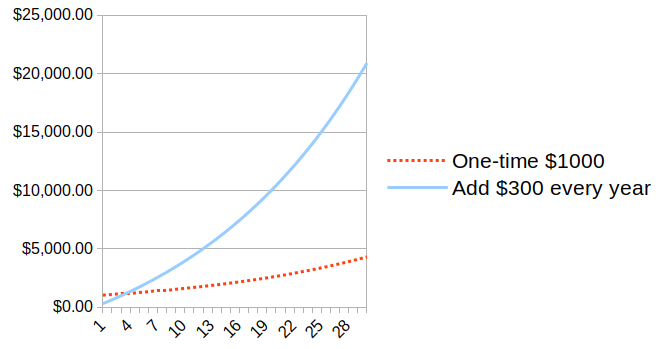

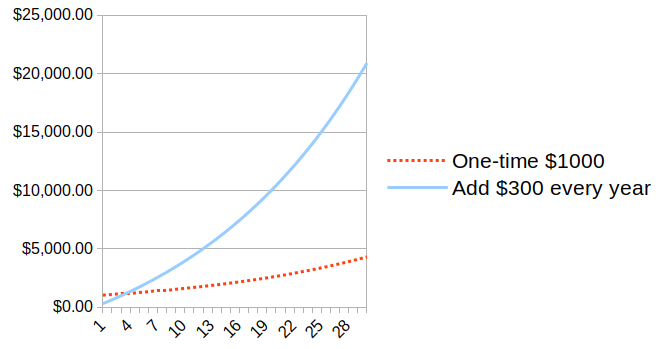

Here’s the difference between the one-time $1000 investment earning compound interest on its own, compared to the $300-a-year geometric series, over 30 years:

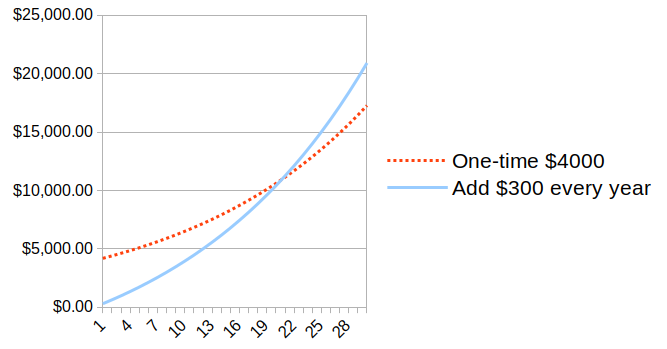

For a better comparison of the shape of the curves, we can bump up the initial one-time investment (the dotted red line) to $4000, so the curves are closer. They intersect after about 22 years.

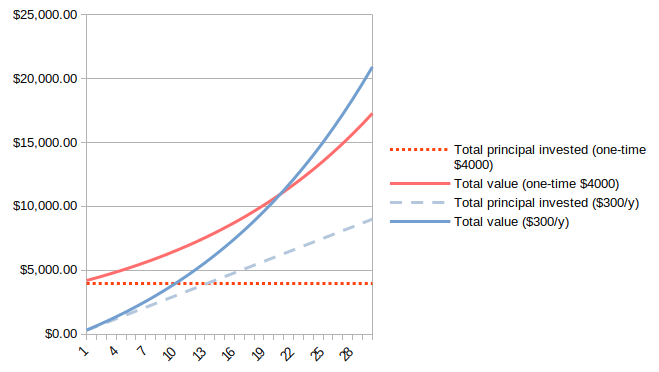

And finally, another important comparison is to show the amount invested vs return-on-investment. Note that the dotted red line - a one-time payment of $4000 - is a horizontal line. Everything between the dotted red line and the solid red line is interest earned.

The blue dotted line - the yearly investments of $300 - slopes upward linearly over time. Because the initial investment is small, it takes sometime before the solid blue line - total value, including interest - pulls away from the value of the principal.

In recent years there’s been interest in incorporating personal finance or “financial literacy” as a basic education subject. Here are two homework problems for you to try out:

Going back to our allegorical high school math class: the personal finance tie-in shouldn’t end with the compound interest formula! Teaching someone how to model saving and spending habits as inputs to a geometric series gives them a powerful tool for financial decision-making.